Of these 15 films, I have now seen 13, all newly or most recently within the past few years, several within the past few weeks or months.

The only two of these lauded works that I have not yet seen are 1948's A Foreign Affair--only recently released on DVD and not yet within my library system--and 1970's The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. (1961's One, Two, Three has also been personally recommended.)

I will give a rundown of the Billy Wilder-directed movies I have seen, and while this will be far from a scholarly treatise, I will try to enunciate why I believe that in terms of entertainment, quality, breadth and socially commentative substance, Wilder's filmography ranks among cinema's all-time best.

And this won't even encompass a number of movies Wilder wrote but didn't direct.

While I respect some movie buff friends who aren't nearly as high on Wilder's oeuvre, or perhaps specific films, in my purview Billy Wilder certainly qualifies as one of the greatest movie directors of all-time.

I won't necessarily champion him above other filmmaking immortals such as Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, John Ford, Ingmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa, Federico Fellini, Stanley Kubrick, Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Sidney Lumet, Steven Spielberg, Quentin Tarantino and others, but I do suggest that for anyone who wishes to explore old, arguably classic movies, there is likely no better crash course than to delve into the best of Billy Wilder's directorial output, as I have.

This isn't merely because of the quality of his films, though I'd agree with AllMovie.com that many are absolutely terrific.

It's because of the breadth of the genres he traversed, and the often daring approach he took to subject matter and societal commentary, something I find sorely lacking in most of today's mainstream Hollywood movies.

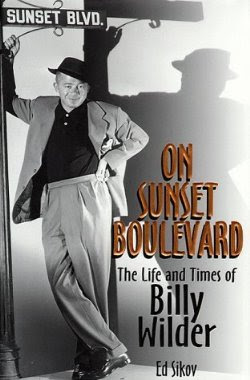

I've yet to dig into the Wilder biography I recently got (On Sunset Boulevard: The Life and Times of Billy Wilder), but I can't help but presume that much of his cinematic verve derived from the circumstances that brought him to Hollywood.

According to Wikipedia, Wilder grew up in Austria and later moved to Berlin, where he eventually began working as a screenwriter. Wilder, who was Jewish, left Germany for Paris in the early 1930's and came to Hollywood in 1933. His mother and stepfather would die in concentration camps, while a grandmother perished within a Jewish ghetto.

Although I have not seen it, it appears that his greatest screenwriting-only success came with 1939's Ninotchka, a comedy starring Greta Garbo directed by Ernst Lubitsch.

On all of the other movies I will cite as having seen and enjoyed, Billy Wilder served as director and co-screenwriter, and in some cases, a producer as well.

1942's The Major and the Minor was technically Wilder's second directorial effort--after Mauvaise Graine, which he didn't write and shot in France in 1934--but his first major Hollywood movie behind the camera after a series of screenwriting efforts. He was championed as director by the film's star Ginger Rogers, who shared the same agent and recently had won an Academy Award for Kitty Foyle.

Co-written with Charles Brackett--who would also collaborate with Wilder on The Lost Weekend, A Foreign Affair and Sunset Boulevard--and also starring Ray Milland, The Major and the Minor is a frothy comedy-romance on which Wilder cut his directing teeth.

The storyline is a tad unsettling as Rogers plays a New York beauty who decides to return to her Iowa hometown, and in order to afford the train fare, poses as a girl under the age of 12. She meets Milland on the train, hides in his sleeping car (with his consent), accompanies him to the military academy at which he teaches, meets his fiance and is courted by a bunch of young cadets, with seemingly no one suspecting anything despite Rogers being over 30 in real life.

AllMovie.com rates the film 4 stars, but while it has its moments, I consider it 'minor' among Wilder's major works. It isn't terrible, but there's likely no need to make a point of seeing it.

The same cannot be said for 1944's Double Indemnity, one of the best examples of film noir ever made. I won't describe much of the plot, since each twist is part of the fun, but Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck get entangled in a unique insurance scheme, which raises the suspicions of the great Edward G. Robinson.

The same cannot be said for 1944's Double Indemnity, one of the best examples of film noir ever made. I won't describe much of the plot, since each twist is part of the fun, but Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck get entangled in a unique insurance scheme, which raises the suspicions of the great Edward G. Robinson. Again, while surely some may disagree, what makes Wilder career so remarkable is that in addition to making one of the preeminent film noir classics, you can also argue that he made one of the best comedies (Some Like It Hot) and courtroom dramas (Witness for the Prosecution), as well as one of the best films about alcoholism (The Lost Weekend), Hollywood (Sunset Boulevard), journalism/media hype (Ace in the Hole), prisoners of war (Stalag 17) and two of the best about adultery (The Seven Year Itch and The Apartment).

The range and versatility to make vastly different films while retaining quality is not only what makes his canon a great starting point in exploring old movies, but what makes Billy Wilder somewhat analogous to The Beatles, Pablo Picasso, Frank Lloyd Wright and Stephen Sondheim as an artist whose talent transcended style/genre and whose brilliance is, in part, defined by the ability to transmogrify so impressively.

It also seems to me that Wilder's films were a bit ahead of their time in terms of their tone and themes. I should also note that, especially compared to many old black & white films, every Wilder movie I watched was acutely and smoothly entertaining. Many may have a hardened edge to them, but they are all easily digestible.

It also seems to me that Wilder's films were a bit ahead of their time in terms of their tone and themes. I should also note that, especially compared to many old black & white films, every Wilder movie I watched was acutely and smoothly entertaining. Many may have a hardened edge to them, but they are all easily digestible. 1945's The Lost Weekend deservedly won four Oscars (Best Picture, director, adapted screenplay and actor) as Ray Milland is outstanding as an unrepentant alcoholic, despite the valiant efforts of his wife (Jane Wyman) and brother (Phillip Terry).

Its look at the tenuous hold of reformation is particularly gripping, and still entirely relevant.

1950's Sunset Boulevard was nominated for 11 Oscars but won just 3--in writing, music and art direction. Yet the story of washed-up Hollywood starlet Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) and her live-in scribe/obsession Joe Gillis (William Holden) is likely regarded as Wilder's greatest critical success. In both of the American Film Institute's (AFI) lists of the 100 best American movies, Sunset Boulevard--which can be considered a film noir classic as well as one of the best movies ever made about movies--ranked among the top 16.

I had scant awareness of 1951's Ace in the Hole until I saw it a few months ago, but was amazed at how prescient--and still acute--it is in depicting how a media frenzy can fuel, well a media (and perhaps secondarily, public) frenzy.

Kirk Douglas is terrific as a disgraced New York reporter who winds up having to beg for a job at an Albuquerque newspaper. His coverage of a man trapped in a collapsed cave brings tourists out in hordes, and with it plenty of questions about journalistic ethics and humanistic morality.

Perhaps due to its cynicism, Ace in the Hole was a critical and commercial flop upon its release, but I give it @@@@@, which is even a half-star more than its AllMovie rating.

1953's Stalag 17 is just as good. A precursor to Hogan's Heroes and conceivably M*A*S*H, the film deals with American airmen holed up in a Nazi prisoner-of-war camp (a.k.a. stalag). William Holden won the Best Actor Oscar for his role, but a strong ensemble cast makes the film--part comedy, part war movie, part suspense thriller--truly outstanding.

Coming after Sunset, Ace and Stalag, the romantic comedies (or some combination thereof) Sabrina (1954), The Seven Year Itch (1955), Love in the Afternoon (1957) and Some Like It Hot (1959) are all lighter fare, but each has its charms including Audrey Hepburn (in Sabrina and Love in the Afternoon) and Marilyn Monroe in the other two.

With its love triangle between Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart and William Holden, Sabrina makes great use of all three of its stars, and while Audrey's pairing with Gary Cooper in Love in the Afternoon isn't nearly as delectable, she's fun to watch, as is Maurice Chevalier as her father, a private detective investigating inveterate playboy Cooper, with whom the virginal Hepburn becomes quite smitten.

Including perhaps the most famous 'posterized' frame of film in movie history, The Seven Year Itch features Monroe at her most fetching, as she coyly titillates the clueless Tom Ewell while his wife is away.

Though not nearly as strident in its exploration of adultery as 1960's The Apartment would be, Seven Year Itch nonetheless tackles a topic that likely was largely taboo in 1955 America.

I also have to imagine that the conceit behind Some Like It Hot--with Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis dressing in drag to travel to Florida with a group of female musicians, including Monroe--was considerably more shocking in 1959 than it feels today, but I can't concur with AFI's ranking of it as the funniest film of all-time.

Still, it seems to stand as Billy Wilder's most famous film, and shouldn't be missed in any exploration of his (or Marilyn's) best work, or even a rather modest survey of classic comedies.

Amidst the Audrey/Marilyn pictures came a wonderful courtroom thriller: 1957's Witness for the Prosecution, starring Tyrone Power and Marlene Dietrich with a wonderful supporting turn by Charles Laughton. AFI ranks Witness as the 6th best courtroom drama ever made in the U.S., and while I best leave the plot entirely out of evidence, my verdict is that you shouldn't miss this one.

Amidst the Audrey/Marilyn pictures came a wonderful courtroom thriller: 1957's Witness for the Prosecution, starring Tyrone Power and Marlene Dietrich with a wonderful supporting turn by Charles Laughton. AFI ranks Witness as the 6th best courtroom drama ever made in the U.S., and while I best leave the plot entirely out of evidence, my verdict is that you shouldn't miss this one.Nor, for that matter, The Apartment, in which Jack Lemmon stars as a bachelor who rises in his company due to letting executives use his convenient flat for extramarital trysts, while an attractive young Shirley MacLaine demonstrates a bit more temerity than one might expect from a woman in her position in 1960. The societal commentary is rather biting in The Apartment, which won Best Picture and earned Wilder his second Best Director Oscar (out of 8 nominations).

I've yet to see One, Two, Three (1961), Irma la Douce (1963) or Kiss Me, Stupid (1964), all rated 3-1/2 stars by AllMovie.com, but liked 1966's 4-star The Fortune Cookie more than I might have expected.

Two years before The Odd Couple, Fortune Cookie was the first film pairing of Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau, who would go on to star in nine more movies together. Lemmon is a football cameraman who gets run over by a member of the Cleveland Browns, played by Ron Rich. Though not seriously injured, Lemmon is convinced by his brother-in-law (a deliciously unscrupulous Matthau) to act as though he is, in order to cash in on a lawsuit. While I lack any real knowledge of the American legal system of the mid-60s, Fortune Cookie plays like a treatise on tort reform, likely well before it became a buzzword.

As I mentioned many paragraphs ago, I have not yet seen the last of AllMovie.com's 4+ star rated Wilder directorial efforts, 1970's The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, nor 1948's A Foreign Affair.

So there is still something for me to explore, as well as much to re-explore in years to come. I am grateful for easy access to most of Billy Wilder's films through the excellent Skokie Public Library, but it shouldn't be hard for anyone to find many of his classics.

When you do, you might be surprised to find that a director who, 11 years after his death at age 95, may best be remembered for his comedies, delved deep--and with unstinting sagacity--into issues like alcoholism, adultery, faded glory, media hype, wartime captivity and more.

If you ever want to scour old movies that may tell you more about the present day than most current films, you could do a lot worse than to work your way through the remarkable oeuvre of Billy Wilder.

While you likely won't be equally wild about each of his films, you may end up considerably wilder about motion pictures in general, and the way they once--and should still--pointedly reflected the world of those who watched them.

No comments:

Post a Comment