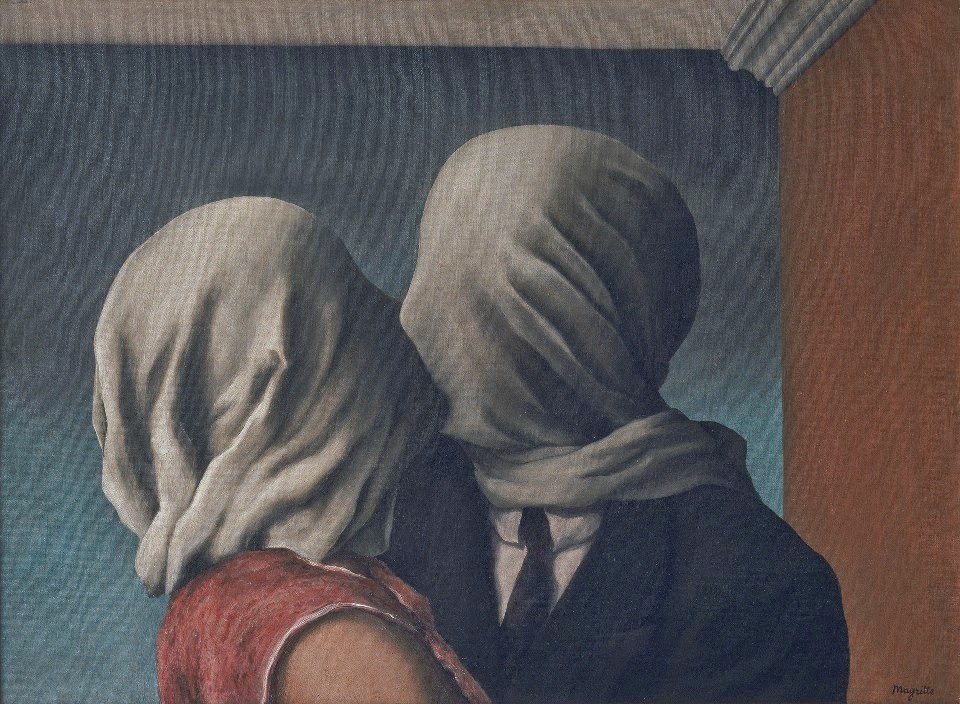

Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926-1938

The Art Institute of Chicago

Thru October 13

@@@@1/2

"Surrealism provides humanity with a method and a mental approach favorable to the investigation of areas that have been deliberately ignored or despised, and yet of direct concern to humanity."-- René Magritte

From "Lifeline" lecture, 1938

There are myriad fine artists whose work I greatly admire and enjoy.

Though he doesn't quite top the list, Belgian surrealist Rene Magritte certainly holds a special place.

His paintings, filled with witty circumventions of convention, have long felt like the ultimate visual equivalents of the verbal puns I dearly love (and with which I have caused Manet an art lover Toulouse-Lautrec of their senses).

After having been introduced to Magritte by Time Transfixed in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, the museum's 1993 retrospective on him was likely the first single-artist exhibition I ever explored--and to this day remains one of the best.

With this fascination going in, the Art Institute's current major exhibition--Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926-1938--was a treat for me, as it focused on the painter's formative years as a surrealist, and one of the very first at that.

From an educational standpoint, the artworks are wonderfully curated and sequenced, with terrific gallery and painting-specific text informing that Magritte--already known in Belgium as a graphic artist and painter of Cubism-inspired works--discovered Surrealism in late 1925, not long after the art movement was begun in Paris by the poet André Breton.

I appreciated all that I learned, and will share some of Magritte's biography and several of his paintings below. Just the ones I include here should aptly illustrate that the extensive exhibition--organized in collaboration with New York's Museum of Modern Art and the Menil Collection in Houston--features enough first-rate works to please any art lover, and especially those beguiled by or curious about René Magritte.

In other words, if you like Magritte heading into the exhibition, you should love what you see and learn.

If you're not familiar with his work, this show is still certainly worth your time--perhaps about 30% of a tourist's first-time visit to the spectacular-across-many-genres Art Institute of Chicago, and a dedicated trek by locals--but may not leave you quite as dazzled by Magritte as I am.

This is largely because some of his more famous and whimsical paintings, making more common use of trompe l'oeil (i.e. optical illusions), came after the exhibition's 1926-1938 time frame.

WikiArt.org's extensive selection of Magritte paintings from his entire career, you can get a better sense of his great later works that follow 1938's Time Transfixed--1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8--many of which I remember from seeing over 20 years ago (and/or reproduced or parodied elsewhere).

But in looking at the best online amalgamation of Magritte I could find, I'm all the more impressed by how many of his major works from 1926-38 the current exhibit includes.

Magritte's first Surrealist works came in 1926 and 1927, before and after his first solo exhibition in Brussels.

The Art Institute's show includes many pieces from these years, not only paintings like The Menaced Assassin (shown above)--which I was intrigued to learn included figures from a popular pre-World War I crime fiction series and a related film--but a rather fascinating full wall of collages in which Magritte utilized images that would become common motifs in his work: bowler hats, theater curtains, mysterious landscapes, jockeys and bilboquets (a child's cup and ball toy), which frequently appear as human stand-ins.

Many of the collages, which also frequently work sheet music into the picture, are untitled, but The Lost Jockey is a prime example. This one is also intriguing due to the accompanying note that one of Magritte's friends identified the jockey as the artist himself. {Note: Painting hyperlinks for works included in the exhibition, beyond those shown in this post, direct to WikiArt.org images.}

Yet, as an example of the kind of keen insights provided by the exhibition's wall text, rather than live in Bohemian Montmarte or otherwise near his friends in the city's center, Magritte opted to maintain his independence by residing in a Parisian suburb.

Though he would return to Brussels in 1930, following the stock market crash that devastated economies--and the art market--worldwide, and would be compelled to seek a job in advertising, during his time in Paris Magritte created numerous notable works that form something of a core to the exhibition.

CBS logo, and his first rendition of "This is not a pipe" (Ceci n'est pas une pipe), officially titled The Treachery of Images.

It was in Paris that Magritte also first concocted his "word image" paintings, in which words--usually in French--would often accompany objects they did not represent.

While these have a certain cerebral appeal, they are far from Magritte's most aesthetically-pleasing work, and a gallery comprising several examples was likely my least favorite in the exhibition.

My favorite "word-image" painting in the show, aside from The False Mirror--which, as the artist noted, depicts a 2-dimension object on canvas that one cannot actually smoke, and therefore is indeed not a pipe--is The Interpretation of Dreams from 1935.

More revelatory from Magritte's time in Paris are two rather novel female nudes--Discovery (1927) and Attempting the Impossible (1928)--which illustrate his "striking discovery of the ability of one object to transform into another," while inviting viewers to "imagine beyond limited meaning."

I also found another strange nude--The Titanic Days--to be rather brilliant in its powerful depiction of a man attacking a woman within the outline of her body.

Magritte would commonly use the female anatomy in rather arresting (and conceivably statement-making) ways, with The Rape (1934) and Representation (1937) contained within the exhibit's 1930-1938 Brussels period.

Although Magritte wasn't painting quite as prolifically during this time, the exhibit has several prime works, including a few I have never seen or don't recall. And with about 10 paintings displayed individually on a series of walls within a hallway, it is in this section that the exhibition's design is most structurally clever.

The Red Model, which merges a pair of boots with human feet, is actually included twice: once on the series of walls and a slightly different version subsequently shown in conjunction with two other paintings representing a 1937 commission from British poet and art collector Edward James (grouped here for the first time since they were removed from James' home during World War II).

One, The Pleasure Principle, envelopes the subject's face in the light of a camera flash, while Not To Be Reproduced shows the mirrored reflection of James' back rather than his front.

This is striking in itself, but even more so due to the progression and hallmarks of Magritte's oeuvre that The Mystery of the Ordinary exhibition reveals.

From an educational standpoint, the artworks are wonderfully curated and sequenced, with terrific gallery and painting-specific text informing that Magritte--already known in Belgium as a graphic artist and painter of Cubism-inspired works--discovered Surrealism in late 1925, not long after the art movement was begun in Paris by the poet André Breton.

I appreciated all that I learned, and will share some of Magritte's biography and several of his paintings below. Just the ones I include here should aptly illustrate that the extensive exhibition--organized in collaboration with New York's Museum of Modern Art and the Menil Collection in Houston--features enough first-rate works to please any art lover, and especially those beguiled by or curious about René Magritte.

In other words, if you like Magritte heading into the exhibition, you should love what you see and learn.

If you're not familiar with his work, this show is still certainly worth your time--perhaps about 30% of a tourist's first-time visit to the spectacular-across-many-genres Art Institute of Chicago, and a dedicated trek by locals--but may not leave you quite as dazzled by Magritte as I am.

This is largely because some of his more famous and whimsical paintings, making more common use of trompe l'oeil (i.e. optical illusions), came after the exhibition's 1926-1938 time frame.

WikiArt.org's extensive selection of Magritte paintings from his entire career, you can get a better sense of his great later works that follow 1938's Time Transfixed--1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8--many of which I remember from seeing over 20 years ago (and/or reproduced or parodied elsewhere).

But in looking at the best online amalgamation of Magritte I could find, I'm all the more impressed by how many of his major works from 1926-38 the current exhibit includes.

Magritte's first Surrealist works came in 1926 and 1927, before and after his first solo exhibition in Brussels.

The Art Institute's show includes many pieces from these years, not only paintings like The Menaced Assassin (shown above)--which I was intrigued to learn included figures from a popular pre-World War I crime fiction series and a related film--but a rather fascinating full wall of collages in which Magritte utilized images that would become common motifs in his work: bowler hats, theater curtains, mysterious landscapes, jockeys and bilboquets (a child's cup and ball toy), which frequently appear as human stand-ins.

Many of the collages, which also frequently work sheet music into the picture, are untitled, but The Lost Jockey is a prime example. This one is also intriguing due to the accompanying note that one of Magritte's friends identified the jockey as the artist himself. {Note: Painting hyperlinks for works included in the exhibition, beyond those shown in this post, direct to WikiArt.org images.}

Yet, as an example of the kind of keen insights provided by the exhibition's wall text, rather than live in Bohemian Montmarte or otherwise near his friends in the city's center, Magritte opted to maintain his independence by residing in a Parisian suburb.

Though he would return to Brussels in 1930, following the stock market crash that devastated economies--and the art market--worldwide, and would be compelled to seek a job in advertising, during his time in Paris Magritte created numerous notable works that form something of a core to the exhibition.

CBS logo, and his first rendition of "This is not a pipe" (Ceci n'est pas une pipe), officially titled The Treachery of Images.

It was in Paris that Magritte also first concocted his "word image" paintings, in which words--usually in French--would often accompany objects they did not represent.

While these have a certain cerebral appeal, they are far from Magritte's most aesthetically-pleasing work, and a gallery comprising several examples was likely my least favorite in the exhibition.

My favorite "word-image" painting in the show, aside from The False Mirror--which, as the artist noted, depicts a 2-dimension object on canvas that one cannot actually smoke, and therefore is indeed not a pipe--is The Interpretation of Dreams from 1935.

More revelatory from Magritte's time in Paris are two rather novel female nudes--Discovery (1927) and Attempting the Impossible (1928)--which illustrate his "striking discovery of the ability of one object to transform into another," while inviting viewers to "imagine beyond limited meaning."

I also found another strange nude--The Titanic Days--to be rather brilliant in its powerful depiction of a man attacking a woman within the outline of her body.

Magritte would commonly use the female anatomy in rather arresting (and conceivably statement-making) ways, with The Rape (1934) and Representation (1937) contained within the exhibit's 1930-1938 Brussels period.

Although Magritte wasn't painting quite as prolifically during this time, the exhibit has several prime works, including a few I have never seen or don't recall. And with about 10 paintings displayed individually on a series of walls within a hallway, it is in this section that the exhibition's design is most structurally clever.

The Red Model, which merges a pair of boots with human feet, is actually included twice: once on the series of walls and a slightly different version subsequently shown in conjunction with two other paintings representing a 1937 commission from British poet and art collector Edward James (grouped here for the first time since they were removed from James' home during World War II).

One, The Pleasure Principle, envelopes the subject's face in the light of a camera flash, while Not To Be Reproduced shows the mirrored reflection of James' back rather than his front.

This is striking in itself, but even more so due to the progression and hallmarks of Magritte's oeuvre that The Mystery of the Ordinary exhibition reveals.

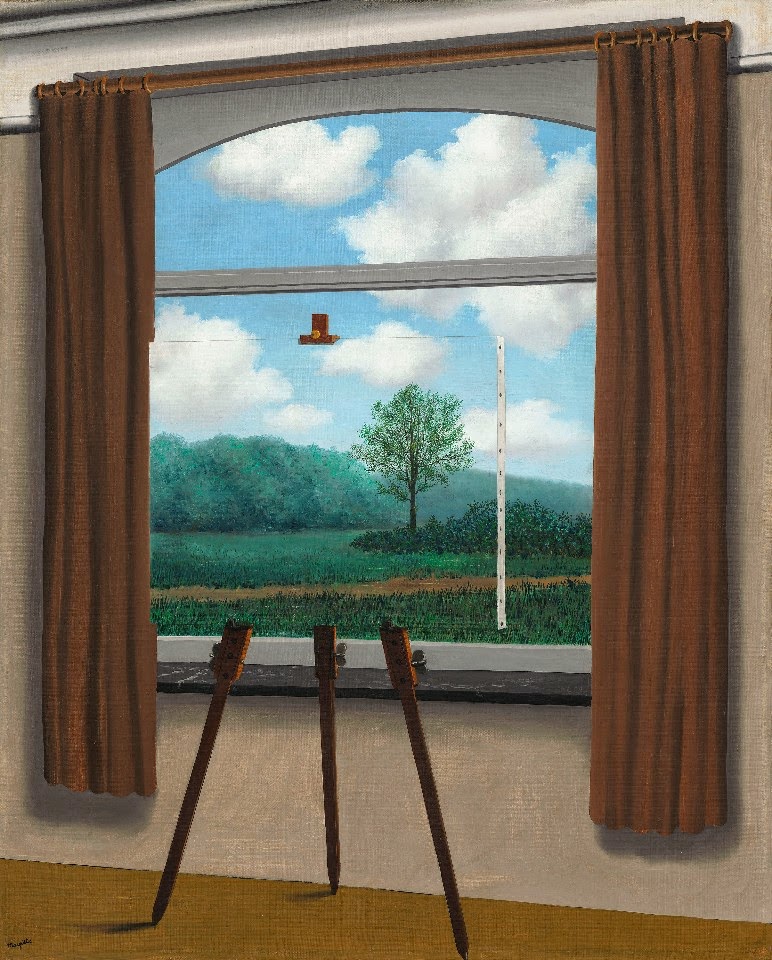

In one of the first galleries, An End of Contemplation, from 1927, was accompanied by the explanation that "doubling was one of Magritte's favorite early strategies to remind us that pictures of things are not the same as the things themselves."

Hence what I meant above in suggesting that this terrific exhibit may be most rewarding to those with the time and inclination to read all the accompanying text--and/or listen to the audio guide, which I didn't--in order to really learn rather than merely look.

Not to suggest that The Mystery of the Ordinary doesn't excel as eye-candy; it does, if perhaps not to the delicacy of the same museum's cherished exhibit of the same artist nearly have my lifetime ago.

But maybe it's my memory that's sugar-coated.

After all, in the superlative surrealistic world of René Magritte, things are rarely exactly as they appear.

---

I'll include a few more works from the Magritte exhibit below, but also suggest that any Art Institute visit before November 9 include the textiles exhibit, Ethel Stein: Master Weaver. I certainly wouldn't have found this exhibition had I not taken the elevator to an under-utilized stretch of the lower level in search of a rest room, but I'm quite glad I did.

The show includes weavings Stein--who is now 96--created from 1982 to 2008 in several different styles, with the self-portrait at left being the most realistic piece amongst several more patterned examples.

Entry to the Magritte exhibit, the Ethel Stein show and other special exhibitions is included in the Art Institute's general admission fee.

---

|

René Magritte (Belgian, 1898–1967). The Healer (Le Thérapeute), 1937.

Oil on canvas; 92 × 65 cm (36 1/4 × 25 9/16 in.). Private collection. © Charly Herscovici – ADAGP – ARS, 2014 |

|

René Magritte (Belgian, 1898–1967). Clairvoyance (La Clairvoyance), 1936.

Oil on canvas; 54 × 65 cm (21 1/4 × 25 9/16 in.). Mr. and Mrs. Wilbur Ross. © Charly Herscovici – ADAGP – ARS, 2014 |

No comments:

Post a Comment